“Diaspora” is a continuation of “An Exile.” That was about departure from Hong Kong and arrival in a new place. This focuses on the period after arrival.

Both are intended as sequel to the book, Liberate Hong Kong: Stories from the freedom struggle, which is about the 2019–2020 protests. That in turn follows As long as there is resistance, there is hope about the period from 2014 to 2018, and Umbrella: A Political Tale from Hong Kong about the 2014 Umbrella Movement.

“Diaspora” will appear in installments. The previous installment was “And shalt be dispersed…”

3. Alaa, Hang-tung, Yasmine: defeat and resistance

We live in hugely reactionary times. My defeat was inevitable…. Unlike me, you have not yet been defeated.

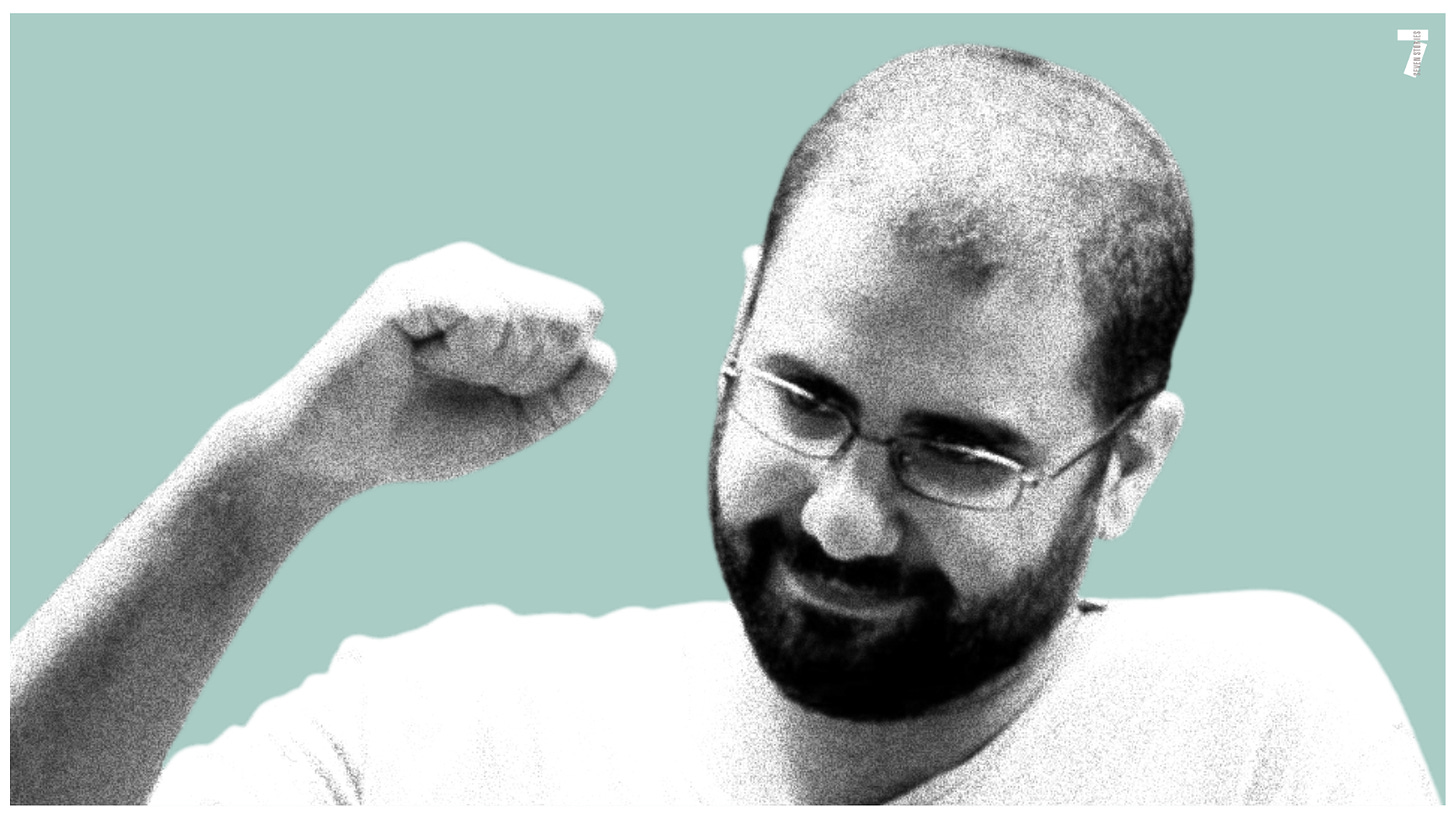

—Alaa Abd El-Fattah, Egyptian revolutionary who has spent most of the past decade since the Arab Spring in prison, along with tens of thousands of other political prisoners

When society is undergoing huge and profound changes, things that are not normal or right become the “new norms.” How to resist the unconscious influence of such great power, how to maintain our ability to judge right from wrong, how to avoid becoming assimilated by the authoritarian logic, how to preserve our autonomy and agency—these are difficult questions we are facing together. We need to stay awake, to constantly reflect on ourselves and to remind each other all the time. We must try our best to live a normal life and speak our mind as much as we can afford. Even when we can’t break the rules, we must ask “why.”

When absurdity has become part of daily life, resistance is what everyone can do in every minute and every hour. Do not underestimate your power. Because every bit of resistance has an effect on the wider society and influences the people around you, helping to prevent them from becoming so easily conditioned. While I am in my small prison, I also need you to help remind me how the normal world works.

—Concluding paragraphs of Chow Hang-tung’s “被制約下必要的反思 | On Conditioning, Friday, November 19, 2021, written in prison

All that's asked of us is that we fight for what’s right. We don’t have to be winning while we fight for what's right, we don’t have to be strong while we fight for what's right, or to have a good plan, or be well organized. All that's asked of us is that we don't stop fighting for what's right.

—Concluding words of Alaa Abd El-Fattah’s speech at the memorial service for his father, Ahmed Seif El-Islam, 23 September 2014, American University in Cairo

They lost in Egypt.

We lost in HK.

It’s as simple as that.

OK, well, not quite.

In fact, I always say the regime’s transformation of HK into a full-blown police state is the surest sign that we are winning: it became so desperate that it believed only extreme measures of imposition and coercion would suffice.

But yeah, we lost.

At least we’re in good company. Most of the popular uprisings over the past decade failed to achieve their immediate objective, which was more or less common to all—democracy, popular sovereignty. The Arab Spring, the Iranian Green Movement, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Cuba, Belarus, Thailand, Russia in various ways at various times, Iran again. Tunisia, Sudan and Burma all appeared to have at least set out on the path to democracy, but initial gains were eventually reversed. Chile may be the only exception, but Chile, while still undergoing a decades-long process of democratization following the Pinochet dictatorship, at least had the good fortune of already being a democracy at the time of the protests, and even it hasn’t managed to clear the last hurdle, passing a post-dictatorship constitution. As Alaa says, “We live in hugely reactionary times.” Democracy is on the defensive in many places, including those already democratic (the United States; Hungary; Poland; India, the world’s biggest democracy; South Africa; Brazil, though the defeats of Trump and Bolsonaro give some hope).

How to come to terms with defeat? If, indeed, that is what it is. Alaa thinks that, for starters, you have to face it squarely, not look away, not avoid it by calling it something other than what it is. He puts it in no uncertain terms—“My defeat was inevitable…”—so that the conclusion can’t be avoided. He makes me question myself: does my tendency to eternal optimism—saying, for example, that the crackdown is really a sure sign we’re winning—amount to avoidance, refusal to face the truth,? Confronting his tough-minded realism, a saying I’ve relied on, to inspire myself and others, could appear little more than wishful thinking or delusion: As long as there is resistance, there is hope. It is not that we see hope and therefore we persist; it is that through our persistence, hope is born. Really? I often find myself wondering how Alaa manages to persevere in prison, under such extremely oppressive conditions, with the awareness that he “has been defeated.”

Alaa himself and Chow Hang-tung as well answer the question by saying, whatever happens, you keep fighting for what is right, you fight against becoming conditioned by injustice, you find whatever ways of resisting that you can, you do not underestimate your power, or come to regard yourself as powerless. Hang-tung, writing from prison, says, “….I reject [the characterization of me as] unfortunate…. It is actually a fortunate thing to be able to fight for one’s own ideas. How many people in the world have such an opportunity? Against the biggest Communist dictatorship in the world, no less. What a challenge. So don’t feel sad for me. We think that way because we regard ourselves as passive victims….” Yes, one mustn’t regard oneself as a victim.

The freedom struggle—whether one has been defeated or is simply preparing for the next round, whether the regime or we are doomed to failure—, is to a great extent psychological, within our own heads. But that is also the only territory of which we remain in control.

Our “defeat” and the suffering inflicted upon us has presented profound challenges to many. I myself am doing ok and feel I have little to complain about. I have always found it of tremendous psychological benefit to recall that most others are far worse off than I. If one is in exile, at least one is safe. If one is in HK, at least one is not in prison. If one is in prison, at least one is not physically tortured. And unlike elsewhere, there have been no mass killings of those who rise up. As Hang-tung says, we have the great fortune to fight for our home, to fight for what’s right. I am the sort who can be happy most anywhere and have often found myself the happiest at the darkest times. For me, simply being alive is a great blessing and joy; encounters with oppression have only served to amplify that deep feeling of gratitude. But then, I’m not in HK, not in prison, am with my family, and we are safe. I doubt I would be able to maintain my equanimity in prison, as people like Hang-tung have appeared to do, and I would be the first to break under torture. But short of prison and torture, I do ok. A modicum of freedom is sufficient.

I worked with Hang-tung in HK Alliance. If there’s anything we have in common it is that we have no illusions about the Communist Party. Down through the years, I’d often thought Hong Kongers were naive about the CCP. From my perspective, Hong Kongers’ ultimate showdown with the Party in 2019 and the subsequent crackdown were not only predictable but inevitable. This is simply a period through which Hong Kongers who want to be free have to pass. Having no illusions about the adversary helped to prepare psychologically for the outcome. I imagine this outlook helps Hung-tung contend with the intense persecution in prison. It’s as if she has been preparing for this moment all along. Oppression is what dictators do, and if you know your dictator, you won’t expect anything else. The CCP will oppress until it falls.

But all around, people struggle with trauma, contend with loss, try to cope with the new dispensation, regard the future with despair. The freedom struggle, it seems, has been internalized.

Not long ago, I came across a new essay by the Egyptian writer, Yasmine El Rashidi. I remembered reading her novel, Chronicle of a Last Summer and compatriot Omar Robert Hamilton’s The City Always Wins after Hong Kong’s 2014 Umbrella Movement. The post-Umbrella period was marked by malaise, confusion, frustration, in-fighting, and their books—about political defeat and disillusionment, about how a shared dashed dream curdles—resonated. I’d also admired her reports from the revolution in the years 2011 to 2014. And then she disappeared. She wasn’t heard from for years. Every now and then, I wondered what had become of her. Her new essay explained much.

The experience of covering the revolution and some of the blowback she received, not least from those she thought were on her side, was so scarring that she tried to spend as much time away from Egypt as possible, even attempting to obtain permanent residency in the US. Her application was denied, all but forcing her to return to Egypt.

“For the majority of those years, I could hardly write about my home country, even as it was the only thing on my mind.”

Those words encapsulated her experience, as well as the wider story of the Egyptian revolution and what followed, a pervasive kind of anguish I recognized well from HKers: it resonates through one’s whole body, at times threatening to incapacitate, wherever one goes and whatever one does, whether at home or abroad—anguish both at one’s personal situation and at the collective suffering of HK people. The trauma becomes the legacy, or at least threatens to, the legacy of a people who have fought so hard for what is rightfully theirs and get in return defeat, oppression, a situation even worse than before.

With great eloquence, El Rashidi describes the difficulty of writing about the movement, about one’s comrades and loved ones.

First, there is the problem that so much has to remain unsaid, unspoken, unnamed due to legitimate fears for the safety of those involved: “…about these intimate stakes and struggles—most often without being able to precisely name or describe them, for fear of what that spotlight may bring and out of concern for the privacy of loved ones, as well as because of the emotional difficulty of living with situations so open-ended and unresolved.” So it is as if so much of one’s story, our collective story must remain untold, or, at best, incompletely and imperfectly told, riddled with holes, gaps, lacunae. So often have I witnessed first-hand or heard of the experiences of others, and thought, This something the world must know about, then realizing that to tell their story would be to endanger them and others.

And then there is the disorientation, depression, anxiety, grief, feelings of loss and bereavement, and that something even beyond that has been taken away, something fundamental that often one can’t quite put one’s finger on—home, time, history, a sense that one can somehow belong in the world, that there is a time and place one can call one’s own, and share with allies and loved ones:

“It became impossible to orient myself again—personally, politically, even in writing—without the aid of medication, and I learned that prescriptions for SSRIs (used to treat anxiety, depression, and trauma) had spiked in Egypt by approximately 70 percent in the past eight years, a fact that pharmacists and psychiatrists I spoke to attributed to the political and social aftermath of revolution.”

“…the feeling remains of being stranded in place, hostage to time… reflecting on the revolution and what it opened up in our lives—beyond activism—and then eventually took away.”

“The revolution—our revolution—with all its political failings, caused its deepest disappointments for my friends and me in the everyday. Our lives have been jostled and dictated by political circumstance.”

“I see now in friends my age the same sense of resignation that I saw in my father. Some have been lost to exile, but some to trauma or depression.”

Around the same time as Yasmine’s essay reached me, Nathan Law also published a piece. One of Nathan’s many great leadership qualities is his openness, his honesty, his willingness to present himself as the vulnerable human being that he and just about everyone else are. Nathan had just come to the end of a period of whirlwind activity. He’d been travelling, he’d published a book. He came “home” to London, which of course had only been his home for a year, and there he was.

He said sometimes late at night while watching the news an uneasiness seized him and he wondered how he could shake the “mental torture.” He has the MLK-style tendency in his writing, as I do too, of “rising to the heights after sinking to the depths,” and sometimes the optimism can seem a little forced, but this time, he said, “I don’t want to end on a high note. I feel that sometimes sadness and anxiety can’t be covered up or wished away with encouragement. In the past I thought I could always deal with these losses, but gradually, try as I might, I felt that my head and heart fell short. When everything is stagnant [referring to the situation in HK and the decreasing attention to it from the rest of the world, which he had written about in the previous passage], you face ever more challenges and doubts—from the outside world, from yourself. Only by carefully exploring the heart and understanding one's own needs and sources of stress can coexistence with this awful emotion be possible. Life is Give and Take. Without giving, there is never any gain; but it is also possible that after giving, no gain will be achieved. We have all invested part of ourselves in Hong Kong, and we have also left part of ourselves in Hong Kong. As a result, we have to face the fact that we are no longer a people without shackles and worries. Some things we have taken for granted must be relinquished in order to move forward with this stone on our back. On another bad Monday, what I really want to say is this: All of you who are heartbroken, you are not alone. In a bleak world, we all have to know ourselves first in order to achieve our goals.”

If Hang-tung can hold steady while in prison, I think to myself, then surely so can the rest of us. Isn’t that the very least we can do? Obviously yes. But at the same time, it is important to allow oneself and others to have feelings of powerlessness, despair and anguish. It is actually part of being a good freedom fighter, and a good human being. One certainly shouldn’t mouth empty words of encouragement when one doesn’t actually feel that way. Sometimes one can run around doing a lot, a whirlwind of activity, and then one stops and takes a step back and wonders, “What was it all for? What good did it do?” There are virtually no actions we can take at this moment in history that will lead directly to any immediate positive outcome for HK. While HK civil society is being systematically demolished, HK is moving further down the list of urgent global priorities. It is a distracted world. That is to be expected. It is one thing to know intellectually that it is a long-term struggle, and another to wake up day after day to that reality.

In a sense, our shared suffering can be considered a kind of gift or even a power. It defines our identity. This is an especially important point to consider now that HK people are, more than ever before, dispersed to the far ends of the earth. I think of a speech Brian Leung gave via video link at a rally in mid-August 2019, at the height of the protests. He’d already left HK after his unmasked speech in the the Legislative Council chamber during the storming of that building on July 1, and his speech makes clear that even back then—now more than three years ago—, he was already thinking about these matters.

He said he thought the reason for such great unity among all HK people who wanted justice and change was that we could stand in each others’ shoes, we could share pain and despair as a result of our common experience of injustice. “I think this is what it means to call ourselves a community,” he said. “We are able to imagine others’ suffering, and willing to shoulder one another’s burdens…. In essence, our identity as Hongkongers exists nowhere else but in our minds. And we reconstitute and strengthen this identity through our every struggle and daily practice. We consider [others in the struggle] as close as our own hands and feet [in fact, “hands and feet”--手足--is the Cantonese term fellow protesters use to refer to one another], even if we have never met them; we take them as our kin even if they are of no blood relation. Every sacrifice made—of blood, freedom, even lives—nurtures this community of suffering…. As long as we keep on shouldering each other’s suffering and having their sacrifice at heart, Hongkongers shall persist as a community, however much we stretch the boundaries of space and time. The fact that tens of thousands of overseas Hongkongers have demonstrated their support to the movement proves my point.”

And since then, in the past three years, upwards of two-hundred thousand HongKongers have left HK, emigrating abroad to escape the clutches of the regime, or simply because they no longer wish to live in a home they no longer recognize, and the “boundaries of space and time” of our identity have been stretched even further. Even spread out to the four corners of the earth, 齊上齊落--“we advance and retreat as one”. That in itself is something of an achievement that one might even say is preparatory to nationhood, though Brian, at least in those still early months of the protests, stuck to the term “community”.

Not long after that speech, he gave an interview in which he said it was precisely due to being so far away from the frontlines that he realized “his only remaining connection with the movement is his imagination of the other protesters’ afflictions. ‘Only then did I realise what really connects Hongkongers, apart from our common language and values, is the pain we share…. A community isn’t bound by geography. Rather, it is created by the language and actions of a people. Human freedom resides in their ability to create, in producing what is unforeseen, which allows them to break’ what can otherwise be seen as the nearly pre-determined or inevitable cycle of history. Brian’s ideas about community and suffering came to be encapsulated in the slogan, ‘Hong Kong belongs to everyone who shares its pain.’”

When Yasmine returned to Egypt after having been denied permanent residency in the US, she found herself spending time with her god-daughter one summer around a pool coincidentally frequented also by Alaa and his son. This was during a brief period of six months of semi-freedom in between his years-long prison sojourns (“semi” because, as a term of his probation, he had to report to a police station every evening and spend the night there, being released again each morning). Both children—Yasmine’s god-daughter and Alaa’s son—were seven years old and got on well, in spite of the fact that Alaa’s son was silent—he didn’t speak. Alaa, of course, had spent most of the boy’s life up to then in prison.

I sense this was a special time for Yasmine. She got a part of herself back and was able to reassemble a vision of her life that made some sense. There was still repressive dictatorship, she was still at loose ends, but perhaps there was also the beginning of being able to work something out from the situation. It wasn’t as if the encounter with Alaa “saved” or “transformed” her, but it inflected the future, bent it at a certain angle, so that, perhaps, other possibilities became discernible even if the exact way out was still elusive.

“We live in hugely reactionary times. My defeat was inevitable.” Alaa’s words sound categorical. But at another time, he explained his statement in a way that sounded more hopeful, or at least more nuanced and multi-faceted:

“I’m in prison because the regime wants to make an example of us. So let us be an example, but of our own choosing. The war on meaning is not yet over in the rest of the world. Let us be an example, not a warning. Let us communicate with the world again, not send distress signals nor cry over ruins or spilt milk; let us draw lessons, summarize experiences, and deepen observations, may it help those struggling in the post-truth era.

“We were, then we were defeated, and meaning was defeated with us. But we have not perished yet, and meaning has not been killed. Perhaps our defeat was inevitable, but the current chaos that is sweeping the world will sooner or later give birth to a new world, a world that will — of course — be ruled and managed by the victors. But nothing will constrain the strong, nor shape the margins of freedom and justice, nor define spaces of beauty and possibilities for a common life except the weak who clung to their defence of meaning, even after defeat.”

Note: All quotes from Alaa are taken from the compilation of his writings, You have not been defeated: Selected works 2011-2021. The reflections on Yasmine El Rashidi were inspired by her essay, “Egypt: Lost Possibilities.”